|

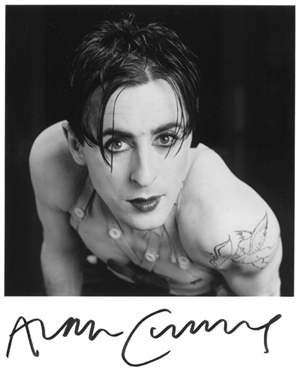

Alan, Thanks for the autograph! |

Roundabout Theatre

Roundabout Theatre

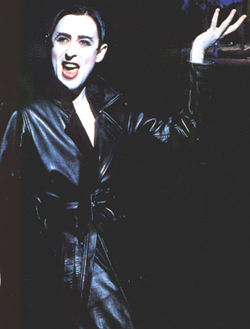

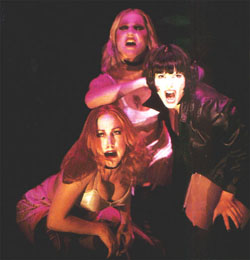

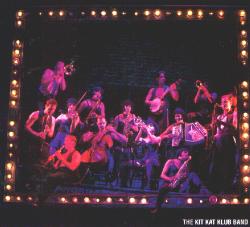

Cabaret at Studio 54

Cabaret at Studio 54

|

|

Enter a world on the verge of chaos, a dark and powerfully decadent universe, where life is celebrated amid flashes of irredeemable evil. It is early 1930s Berlin: Germany faces economic collapse; unemployment numbers over six million; bread lines stretch for blocks in cities throughout the land; hunger, poverty and fear are everywhere.

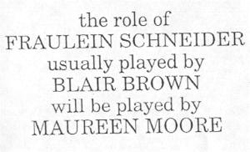

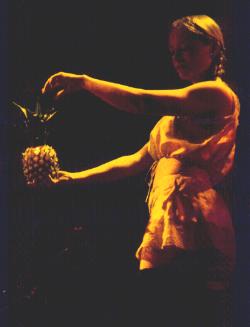

The hard-pressed population is desperate for a way out of its misery. With the weakened Weimar government offering little relief, the political drama moves feverishly to the extremes: Communists on the left; National Socialists-the Nazi Party-on the right. As the economy tumbles further toward catastrophe, the strong-arm appeal of the Nazis, with their nationalistic, slogan-ridden tactics of terror, gradually strengthens. Violence and hate shake the very roots of German society. The madness is about to begin. Christopher Isherwood, a young English writer who comes to Germany in 1921 to explore the city’s seedy underworld, observes the unfolding tragedy. He immerses himself in Berlin’s decadent sub-culture and raunchy night scene, where sexual depravity and moral despair reign. He befriends a colorful cast of Berlin misfits and expatriates, who fail to foresee the brutal impact the Nazis will soon have on the country. Isherwood’s acute, first-hand observation of pre-World War II Germany, which he details in his diary, form the basis of The Berlin Stories (1946), a collection of closely linked sketches that, with understated clarity, portray the hopes and fears of a soon-to-disappear world. It is fitting that the stories, grouped in two volumes, are titled The Last of Mr. Norris (1935) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939) – both, prophetic references to the coming destruction as well as satirical tributes to "those individuals whom respectable society shuns in horror," he writes. "From my window, the deep solemn massive street. Cellar-shops where the lamps burn all day, under the shadow of top-heavy balconied facades, dirty plaster frontages embossed with scrollwork and heraldic devices. The whole district is like this: street leading into street of houses like shabby monumental safes crammed with the tarnished valuables and secondhand furniture of a bankrupt middle class." - Goodbye to Berlin One of Isherwood’s most unforgettable characters, Sally Bowles, inspired playwright John van Druten to adapt The Berlin Stories for the theater. The play, I Am a Camera, was produced in New York in 1951, with Julie Harris in the lead role. A film version was produced in 1955. Then, in 1966, Hal Prince transformed the enduring work into the groundbreaking musical, Cabaret, with Joe Masteroff’s book and a magical score by the team of John Kander and Fred Ebb. Bob Fosse’s acclaimed move version of the musical followed in 1972, starring Joel Grey and Liza Minnelli in what would become their signature performances. However, it is the current Broadway revival, directed by Sam Mendes and choreographed and co-directed by Rob Marshall, that most dramatically evokes the period’s darkness and impending doom. Through exhaustive historical research and adherence to original source materials, they bring the sordid demimonde of pre-Nazi Germany into sharp focus. At the same time, the Roundabout Theatre Company production conjures a distinctly modern vision, creating what Vincent Canby of the The New York Times calls a "stunning revival, a production to keep you spellbound," one that "generates the excitement of something brand new." Turning the entire theater into the Kit Kat Klub, an authentic recreation of a Berlin nightclub, Mendes and Marshall transport the audience to Weimar Germany. With many theatergoers actually sitting at café tables, they viscerally experience an evening of inspired musical theater. The entertainment begins before the lights go out, as several band members/chorus girls drift on stage, lasciviously warming up their near-naked, tattooed and somewhat bruised bodies. The emcee cum tour guide generates enough high-energy sleaze to brake all time barriers, breathing new life into Kander and Ebb’s heartwarming - and heartrending -score. Ironically, this Cabaret achieves its immediacy by remaining ever loyal to history. For example, the production draws directly from the works of the German Expressionists, a school of painters, who, united in their shared search to portray man’s spiritual condition, imbued their art with a growing awareness of the violence and inhumanity of the era. Specifically, the production turns to the works of two renowned artists, George Grosz and Otto Dix. Said Grosz of his art at the time: "I felt the ground shaking beneath my feet, and the shaking was visible in my work." In fact, a Dix painting directly inspired the stage’s prominent tableau that cleverly frames the show’s versatile orchestra members. As the evening progresses, the presence of the encroaching Nazi movement mounts. In 1930, the Nazi party achieves a triumphant success in the national elections, convincing millions of ordinary Germans, as well as many business and military leaders of its inevitable rise. After all, more and more people believe that despite the party’s brown-shirt underbelly of demagoguery and vulgarity, it might be just what is needed to restore the old Germany-economically, politically and socially. In 1933 Adolph Hitler is elected Chancellor of the Third Reich. Through subtle outbursts of violence and rising overtones of anti-Semitism, the frightening, new reality begins to invade the everyday existences of the Cabaret cast, whose lives and loves are brilliantly interwoven with may of the show’s classic nightclub songs. They include Maybe This Time, Money and If You Could See Her. Perhaps it is this juxtaposition-of the characters’ vulnerability, warmth and caring alongside the marching forces of evil-that not only captures the shocking extremities of pre-war Germany, but that also lends Cabaret its timelessness and its humanity. In his introduction to The Berlin Stories, Isherwood describes his return to Germany in the early-1950s: "…I marveled, as one always does, at the individual’s ability to be himself and survive, amidst a huge undifferentiated military mess." And with the help of Frl. Schroeder, his "dear friend" and former Berlin landlady, he arrives at a relative peace with the past. With simple wisdom she explains the secret of her survival and the war’s only moral: "Somehow or other, life goes on in spite of everything." Still, little can prepare audiences for the chilling scene that awaits them at the end of this Cabaret production. The viewer, fully aware for the nightmare that would become the Third Reich, is left with a dazzling and powerful reminder about one of history’s darkest hours: Victim, participant or witness-no one is exempt from the experience. Leave all your troubles outside! So-life is disappointing? Forget it! We have no troubles here! Here life is beautiful… - Cabaret Program, 1999. |

|

|

[TOP] [SONG PAGE] [NYC Photos Menu]